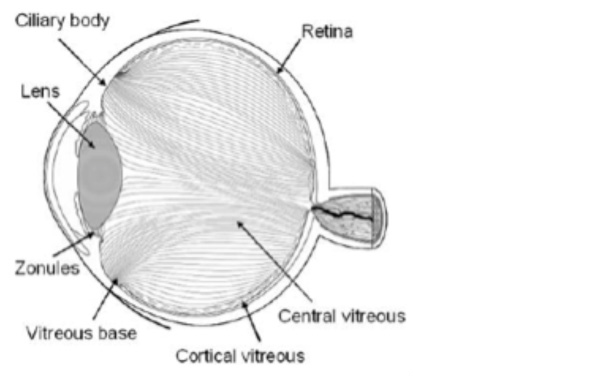

The vitreous is a clear jelly-like substance that fills the inside of the eye. The vitreous aids in focusing light on the back of the eye and helps to supply nutrients to the inside of the eye. The vitreous is made up of 99 percent water and 1 percent collagen fibers. The collagen fibers give the vitreous its jelly-like consistency. The area surrounding the vitreous is called the vitreous cortex. The vitreous cortex is essentially a thin membrane (similar to a plastic bag) which holds the jelly-like vitreous in place.

A posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) occurs when the vitreous cortex separates from the retina (the nerve layer on the back of the eye). A PVD occurs because of two normal changes that happen to the vitreous as the eye ages: First, the collagen fibers in the vitreous begin to clump together, causing pockets of the vitreous to becomes more liquid (less jelly-like). Second, the attachment between the vitreous cortex and the retina weakens.

A PVD is a fairly common occurrence, with approximately 25% of people experiencing a PVD at some point in their life. A PVD often gives rise to two symptoms – floaters and flashes.

- Floaters are normally caused by the detached vitreous cortex casting a shadow on the back of the eye. People often describe floaters as a “spider’s web” or “fly” in front of their vision.

- Flashes (or photopsia) describe the sensation of sparkling lights off to the side of a person’s vision. Flashes are caused by the vitreous cortex tugging on the peripheral retina (where it is more firmly attached).

Flashes normally disappear after a few days. Floaters, however, do persist for the rest of the person’s life, although (with time) the brain normally learns to ignore them.

Although it can seem quite distressing a PVD on its own will not cause any damage to your eyes. However, flashes or floaters can be caused by more serious eye problems, and it is therefore important to have your eyes tested by an optometrist if you notice either of these symptoms. The optometrist will check for any abnormal adhesions between the vitreous cortex and the retina, including an examination for any holes, tears, degenerations, or detachments of the retina. To do this, the optometrists will need to dilate your pupils to conduct a thorough examination of the ‘back of your eyes’. Once you have had your eyes tested and the optometrist is happy that you have no other risk factors for a retinal detachment then all you need to do is monitor your eyesight for any unusual changes, including any increase in the size or number of floaters or the development or worsening of flashing lights in your vision. If you do notice these or any other changes in your vision, please contact your optometrist promptly.